The Untold Truth Of The Sydney Opera House

We all have our own reasons for wanting to visit Australia. Maybe it's your dream to scuba dive on the Great Barrier Reef and experience one of the natural wonders of the world in person. Maybe you want to camp under the stars in the deep red dirt of the Australian outback and see what it truly feels like to be in the real middle of nowhere. Maybe you want to visit Sydney to see if you can find a P. Sherman at 42 Wallaby Way for yourself.

Something that is on all of our lists, however, is seeing the iconic Sydney Opera House in person. According to UNESCO, the World Heritage Convention calls it one of the most influential buildings in architecture. Set like a sailboat billowing out onto Sydney Harbour, the opera house is a pillar of culture for the whole of Australia. However, it's also a building steeped in legend and controversy. Here is the untold truth of the Sydney Opera House.

The opera house sits on Bennelong Point

The Sydney Opera House sits on a very important place on Sydney Harbour: Bennelong Point. First, it is located just across Circular Quay from the iconic Sydney Harbour Bridge, which links the North Shore with the city's central business district. Together, these two structures form what is Australia's most iconic skyline, so it's a good thing they are so close together. Second, Circular Quay is one of the busiest transportation stops in the city of Sydney, as ferries, trains, buses, and light rail all stop there (via AECOM).

According to the Pocket Guide to Sydney, Bennelong Point was named after a man called Woollarawarre Bennelong. He was a senior member of the Eora Nation when British colonizers first arrived in the area in 1788. The Sydney Opera House honors Bennelong and the Eora Nation with informational plaques on the grounds of the opera house concourse. In addition, a "Welcome to Country," or land acknowledgment, is performed before all events that take place there.

The design was chosen through a competition in 1956

In February 1956, Joseph Cahill, the premier of New South Wales, announced a competition to build a national opera house at Bennelong Point. He invited everyone, not just Australians, to submit their designs for consideration. According to Time Out Sydney, over 200 designs were submitted by the time the competition drew to a close. These included a large concrete, brutalist design submitted by a group from Philadelphia.

Judging the competition was a panel of four men, all architects themselves: the chair of architecture at Sydney University, H. Ingram Ashworth; Dr. J. Leslie Martin; NSW Government Architect Cobden Parkes; and Eero Saarinen. There is a fun myth about how the winner was chosen from among the many entries. Legend says that Saarinen had other commitments and showed up about 10 days after the judging of entries had already started. When he walked in, he was overwhelmed by the sheer amount of entries that needed to be sorted through. So, he walked over to a pile, pulled a design out at random, and declared it to be the best by far. It's the design the committee eventually chose, but he had actually pulled it from the reject pile (via Sydney Opera House).

Jørn Utzon from Denmark won the competition

The design that Eero Saarinen allegedly plucked from the reject pile belonged to Jørn Utzon, a young architect from Denmark. According to The Sydney Morning Herald, he heard about the competition when he ran into a group of girls from Sydney at an equestrian event in Sweden. When he won, it was his daughter that told him. "My daughter Lin ran to tell me when I was out walking in the forest," said Utzon. "She threw her bicycle in a ditch and said now I have no excuse not to buy her a horse."

Saarinen was very involved in the beginning stages of construction for the opera house, but over time, his relationship with the New South Wales government and other stakeholders in the project began to break down. The budget for the project ballooned and the timeline kept dragging on and on, leading to flaring tempers and many disagreements. So, unfortunately, Utzon never saw the completed project as he left Australia well before the opera house was finished, never to return. In fact, when the opera house was officially opened in 1973, his name was not even mentioned in the proceedings (via Smithsonian).

Construction went 95 million dollars over budget

According to Courier Mail, the original cost estimate to build Sydney Opera House was $7 million AUD. However, there was a major budget blowout, so the final cost was actually $102 million AUD. The state of New South Wales raised most of the funds through the state lottery. Critics claim that the reason for the massive overshoot of the budget is that it was lowballed in the first place. Had the stakeholders budgeted better at the beginning, the pricing would have been more realistic from the start.

However, since then, the opera house has more than earned back the debt to build it. It brings in an estimated $775 million AUD to the economy in Australia each year through tourism and cultural events. In addition to this, the project also served as a bit of warning for New South Wales, and Australia in general, on how to better plan for infrastructure projects. "The shells in Sydney Harbour have placed Australia on the global map like nothing else. But given the costs involved — the destruction of the career and oeuvre of an undisputed master of 20th-century architecture — Sydney provides a lesson in what not to do," Danish economic geographer Bent Flyvbjerg told Harvard Design Magazine.

Construction took 14 years

The project not only cost substantially more than planned, but its construction dragged on forever. In the end, it took 14 years to finally finish the building. According to Britannica, most of the delays came from attempting to translate elements of Jørn Utzon's theoretical design into structurally sound work that would be safe in the real world.

In addition, when Utzon left the project after poor communication and project management, the entire plan for the main concert hall was completely changed. "The problem with our concert hall is that it was originally designed to have a grid, a flying system [theatrical rigging] above the stage so it could be used for opera and plays. It was called a multipurpose hall," says Louise Herron, the Opera House's chief executive (via The Guardian). It was changed to favor symphonies instead which were said to be more popular at the time. Understandably, all of the infighting significantly lengthened the timeline for completion.

The concert hall had to be refitted to work as a performance space

Because of all the back and forth during its initial construction, the opera house actually didn't work very well acoustically for many years. There have been many renovations to try and make it work. According to The Guardian, staff did things like upgrading the PA system and installing heavy drapes to hang over the wood paneling to try to absorb some of the noise. However, most guests would agree that these were band-aids that didn't really address the underlying problem.

"The shows that we currently put in there were never in the initial scope for the hall," Andrew Mackonis, a production manager, told The Guardian. "Essentially it's designed to be a big echo chamber, and that's the opposite of what you want when you're doing an amplified event. You want the space to be as dead as possible." The main hall closed in early 2020 for a two-year renovation, but construction was delayed due to COVID-19 (via The Sydney Morning Herald).

The opera house's roof is actually tiled

Since most of us are used to seeing the roof of the Sydney Opera House in pictures taken from far away, you might be surprised to learn that its iconic sail-shaped roof is actually not one solid piece of material. In fact, according to Architectuul, the roof is actually made up of over a million small tiles arranged in a repeating chevron pattern.

The reason for this design choice isn't just aesthetics, which makes sense because you have to get really close up to the structure to even notice the tiling. From far away, it just looks like solid metal or stone. The main reason is that the roof is thought to be self-cleaning. Rain falls down through the network of tiles and it is supposed to take most of the grime and debris that builds up over time down with it. In addition, the smaller tiles are meant to catch the light and cause dazzling reflections for everyone across Sydney Harbour to enjoy (via Rosteel Roofing).

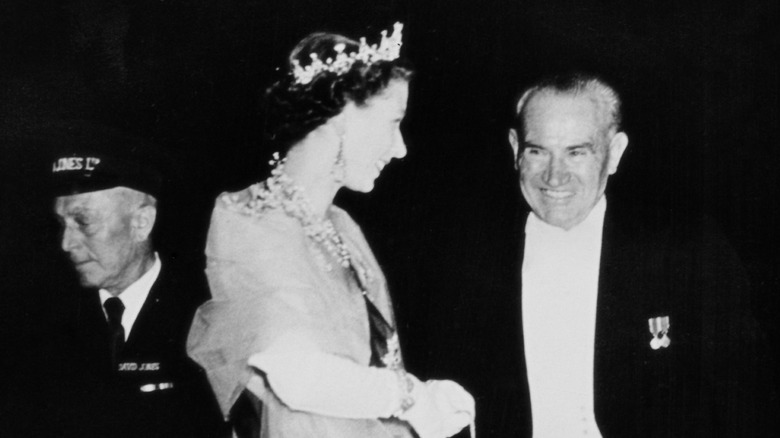

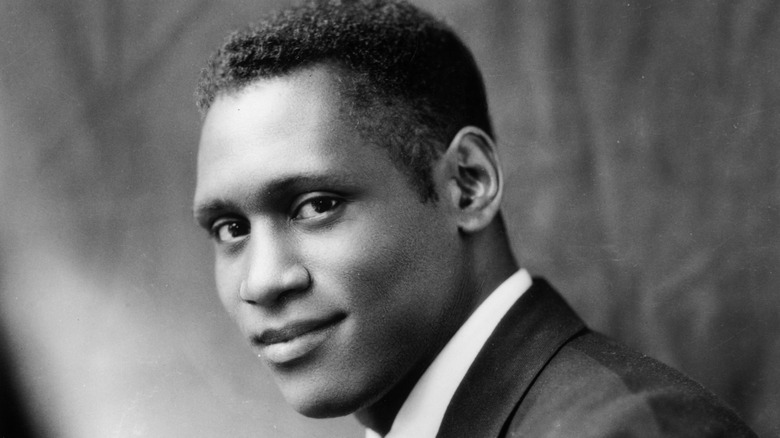

Paul Robeson was the first to perform at the opera house, unofficially

When the Sydney Opera House was finally completed, there was much buzz and anticipation around who the opening act would be. However, unofficially, that title actually belongs to singer Paul Robeson — and he nabbed the spot long before the building's dedication by Queen Elizabeth II. According to NFSA, Robeson is an American who sang for construction workers at the opera house on their lunch break one afternoon in 1960. He was in Australia for a tour at the time, and his appearance on the concrete foundations of the building was organized by the Building Workers' Industrial Union as a treat for those working on site.

He sang the powerful song "Ol' Man River" from the 1927 musical "Showboat." Robeson was a staunch defender of civil rights, so his choice about the triumphs of African Americans in the face of adversity is a powerful one.

The carpet inside the lobby is actually bright purple

A unique feature of the Sydney Opera House is that the carpet in the building's lobbies and foyers is actually bright purple. It's a stark departure from the more typical velvet red that other music halls use, so it's usually a nice surprise for guests who have the opportunity to visit in person. However, for some, the color purple is a bad omen and it can be distressing.

One such person in this camp was the famous opera singer, Luciano Pavarotti. According to The Hamilton Spectator, Pavarotti had a deep fear of purple and didn't like it near him when he performs. "Mr. Pavarotti is very superstitious about the color purple," Gabe Macaluso, manager of a concert venue, told the Spectator before Pavarotti's death in 2007. "It reminds him of death. The staff had to pick all the purple flowers out of the vases." So, if you take a tour of the Sydney Opera House, the staff will always be sure to mention that when Pavarotti was going to be in town, they tried to cover it up so as to not spook him (via Sydney Expert).

The concert hall is kept at a specific temperature

When there are any instruments present on stage in a concert hall, the temperature in the room, as well as the level of humidity, are critical to the success of the performance. According to Condair, this is because the wood in pianos, many woodwinds, and even many string instruments are very sensitive to air. They are what is called hygroscopic, which means that when they are completely dry, they can shrivel up. This can negatively impact their sound, so the air around them needs to be a little damp to ensure peak performance.

The key to a well-run performance venue is allowing the instruments the amount of humidity they need without making the performers and audience feel like they are sitting inside a tropical rainforest. To achieve this balance, the Sydney Opera House keeps its hall at an even 22.5 degrees Celsius for a happy medium — about 72.5 degrees Fahrenheit (via Sydney Opera House). So, if you attend a performance, be sure to bring a sweater, just in case.

The building's climate control is powered by Sydney Harbour

The Sydney Opera House has a unique system in place to maintain the correct temperature needed for peak performance. According to the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, a little-known fact about the building is that all of its heating and air conditioning system is actually powered by cold seawater pulled directly from Sydney Harbour. This reduces the building's reliance on electricity, thus lowering its overall carbon footprint. "As the symbol of modern Australia, the Opera House's role has a responsibility to lead by example. Climate Active certification enables us to reduce our own environmental impact and inspire other organizations to take action," Emma Bombonato, Sydney Opera House Environmental Sustainability Manager, told Climate Active.

This program was introduced to the opera house in 2017 and resulted in a 9% energy reduction. Overall, the opera house aims to reach carbon neutral status by its 50th anniversary in 2023.

There is a bar and restaurant attached to the opera house

If you are hungry before a show at the Sydney Opera House, there is no need to worry — the Opera Bar is attached to the lower concourse of the building. According to CNTraveler, it's a great place to grab a bite before a show. The venue is entirely outside and stretches out beside the harbor on a multi-level sunken panel. There is seating under an overhang, but the venue also provides umbrellas for guests wanting to protect themselves from the wrath of the Australian sunshine.

One of the best things about Opera Bar is that it is adored by both tourists and locals alike. So, whether you are spending the evening seeing "Madame Butterfly" at the theater or just want the chance to rub shoulders with some real Aussie blokes, this is the best place to do it. Food and drinks here are priced on par with the rest of the city, so you won't pay a tourist surcharge. Go at sunset for the most stunning views as the light fades from Sydney Harbour.

Opera Bar employs dogs to help keep the seagulls away

One thing that most people think of when they consider enjoying an appetizer near the ocean is seagulls. The flying pests often have to be warded off from stealing french fries, or even worse, using the restroom on your table. However, the Sydney Opera House and Opera Bar have joined forces to solve this problem once and for all. According to Reuters, they've hired local dogs to keep the birds away. It's all part of an initiative to help diners enjoy their meals.

The program began in 2018 and management states that there has been an 85% reduction in complaints about seagulls since then. "It's been a game changer, you could say, in hospitality," manager Sammy McPherson told Reuters. "We're not having to chase after birds and the amount of food replacement, broken glasses, broken plates. It's been absolutely amazing." There are more than 10 dogs in the program who work across multiple shifts. They wear vests to identify them and are always accompanied by a handler.

The Opera House is also an art installation

Vivid is an annual festival of lights that takes place throughout Sydney during the early winter months. According to Vivid Sydney, the opera house is one of the major sites for the festival. Since the iconic sails of the opera house are a bright white, they make the perfect blank canvas for local artists to project digital works onto.

For example, the structure was used to pay homage to Australia's First Nations people in 2022. An installation known as "Yarrkalpa — Hunting Ground" was put together by Martu Artists and Curiious. The work brought the Parnngurr community and its surrounding landscape to life. In-person visitors were treated to bright, swirling visuals. And, once they got close enough, the presentation was accompanied by a soundtrack by Electric Fields, which featured the vocals of the Martu Artists involved in the work.